The United States is experiencing an extreme teenage mental-health crisis

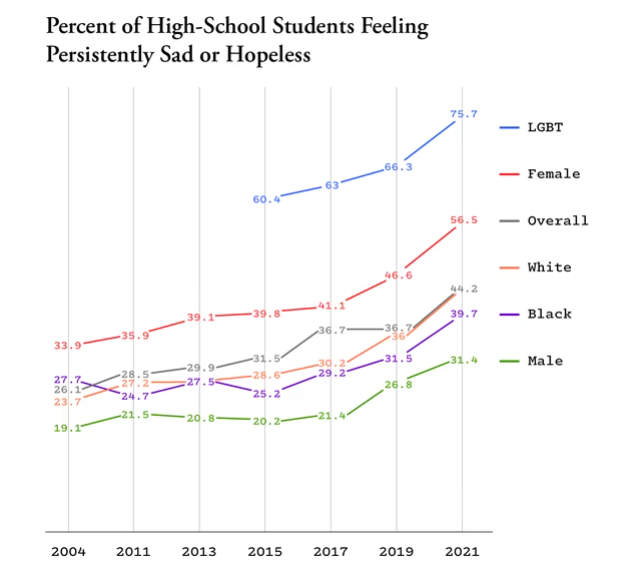

From 2009 to 2021, the share of American high-school students who say they feel “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” rose from 26 percent to 44 percent, according to a new CDC study. This is the highest level of teenage sadness ever recorded.

The government survey of almost 8,000 high-school students, which was conducted in the first six months of 2021, found a great deal of variation in mental health among different groups. More than one in four girls reported that they had seriously contemplated attempting suicide during the pandemic, which was twice the rate of boys. Nearly half of LGBTQ teens said they had contemplated suicide during the pandemic, compared with 14 percent of their heterosexual peers. Sadness among white teens seems to be rising faster than among other groups.

But the big picture is the same across all categories: Almost every measure of mental health is getting worse, for every teenage demographic, and it’s happening all across the country. Since 2009, sadness and hopelessness have increased for every race; for straight teens and gay teens; for teens who say they’ve never had sex and for those who say they’ve had sex with males and/or females; for students in each year of high school; and for teens in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

So why is this happening?

I want to propose several answers to that question, along with one meta-explanation that ties them together. But before I start with that, I want to squash a few tempting fallacies.

The first fallacy is that we can chalk this all up to teens behaving badly. In fact, lots of self-reported teen behaviors are moving in a positive direction. Since the 1990s, drinking-and-driving is down almost 50 percent. School fights are down 50 percent. Sex before 13 is down more than 70 percent. School bullying is down. And LGBTQ acceptance is up.

The second fallacy is that teens have always been moody, and sadness looks like it is rising only because people are more willing to talk about it. Objective measures of anxiety and depression—such as eating disorders, self-harming behavior, and teen suicides—are sharply up over the past decade. “Across the country we have witnessed dramatic increases in Emergency Department visits for all mental health emergencies including suspected suicide attempts,” the American Academy of Pediatrics said in October. Today’s teenagers are more comfortable talking about mental health, but rising youth sadness is no illusion.

The third fallacy is that today’s mental-health crisis was principally caused by the pandemic and an overreaction to COVID. “Rising teenage sadness isn’t a new trend, but rather the acceleration and broadening of a trend that clearly started before the pandemic,” Laurence Steinberg, a psychologist at Temple University, told me. But he added: “We shouldn’t ignore the pandemic, either. The fact that COVID seems to have made teen mental health worse offers clues about what’s really driving the rise in sadness.”

Here are four forces propelling that increase.

Recent Comments